“Says a lot, DOESN’T IT?” Sharyl Attkisson shares leaked internal email that’s SO VERY damning for John Brennan

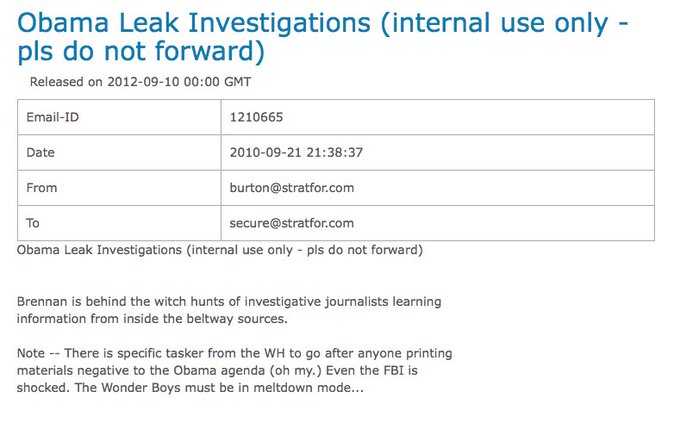

You know when an email says, ‘Internal use only, please do not forward,’ that what’s inside is going to be (good!) very damning for SOMEONE, somewhere. And in this case with the email leaked in Sharyl Attkisson’s tweet, that someone is John Brennan (with a dash of Obama).

“A specific ‘tasker’ from the White House to go after anyone printing materials that were negative to the Obama agenda.”

But Chris Cillizza promised us there was no bias in the media.

Even the FBI is shocked … huh. And who the heck are these ‘Wonder Boys’? So many questions.

Seems that way, more and more.

But Trump and stuff.

At least.

Whoa.

This editor still doesn’t understand why people like Brennan don’t lose that clearance the moment they are no longer in the official position. It’s not like people who lose, quit, or switch jobs get to keep accessing their old jobs after they’re gone.

Revoke it. No brainer.

Something stinks.

All of this being said, we wouldn’t hold our breath on Brennan answering for anything if we were you. These people are like Teflon …

_____________________________________________________________________

The Untouchable John Brennan

How did the candidate of hope and change turn into the president of secret kill lists, drone strikes hitting civilians, and immunity for torturers? The answer may lie in his relationship with the CIA director, a career bureaucrat turned quiet architect of a morally murky national security policy who isn’t going to let a little thing like getting caught spying on the Senate bring him down.

Shortly before 9 a.m. on March 11, 2014, Dianne Feinstein, the 80-year-old chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, walked into the Senate chamber with a thick stack of papers and a glass of water. The Senate had just finished a rare all-night session a few minutes earlier, and only a handful of staffers were left in the room. Feinstein had given thousands of speeches over her career, but none quite like this.

“Let me say up front that I come to the Senate floor reluctantly,” she said, as she poked at the corners of her notes. The last two months had been an exhausting mix of meetings and legal wrangling, all in an attempt to avoid this exact moment. But none of it had worked. And now Feinstein was ready to go public and tell the country what she knew: The CIA had broken the law and violated the Constitution. It had spied on the Senate.

“This is a defining moment for the oversight of our intelligence community,” Feinstein said nearly 40 minutes later, as she drew to a close. This will show whether the Senate “can be effective in monitoring and investigating our nation’s intelligence activities, or whether our work can be thwarted by those we oversee.”

Two hours later and a few miles away at a Council on Foreign Relations event near downtown Washington, the CIA responded. “As far as the allegations of, you know, CIA hacking into Senate computers,” CIA Director John Brennan told Andrea Mitchell of NBC News, shaking his head and rolling his eyes to demonstrate the ridiculousness of the charges, “nothing could be further from the truth. I mean, we wouldn’t do that.”

Brennan was 58, but that morning he looked much older. He’d hobbled into the room on a cane following yet another hip fracture, and after some brief remarks he eased himself into a chair with obvious discomfort. Two years earlier in a commencement address at Fordham University, his alma mater, Brennan had rattled off a litany of injuries and ailments: In addition to his hip problems, he’d also had major knee, back, and shoulder surgeries as well as “a bout of cancer.” Years of desk work had resulted in extra weight and the sort of bureaucrat’s body that caused his suits to slope down and out toward his belt. “I referred the matter myself to the CIA inspector general to make sure that he was able to look honestly and objectively at what the CIA did there,” Brennan said. “And, you know, when the facts come out on this, I think a lot of people who are claiming that there has been this tremendous sort of spying and monitoring and hacking will be proved wrong.”

Mitchell, who had already asked him two questions about the allegations, pressed again. “If it is proved that the CIA did do this, would you feel that you had to step down?”

Brennan chuckled and stuttered as he tried to form an answer. Two weeks earlier, he had told a dinner at the University of Oklahoma that “intelligence work had gotten in my blood.” The CIA wasn’t just what he did; it was his “identity.” He had worked too hard to become director to give up without a fight. “If I did something wrong,” Brennan eventually told Mitchell, “I will go to the president, and I will explain to him exactly what I did, and what the findings were. And he is the one who can ask me to stay or to go.”

But Obama was never going to ask for his resignation. Not then, and not months later when the CIA inspector general’s report came back, showing that the agency had done what Feinstein claimed. Brennan was Obama’s man. His conscience on national security, and the CIA director he’d wanted from the very beginning. Not even a chorus of pleas from Democratic senators, members of Obama’s own party, made any difference. John Brennan would stay, the untouchable head of America’s most powerful intelligence agency.

Brennan has been many things: a CIA official, a CEO, and even, briefly, a television pundit. He was a top official at the CIA during the torture years of the Bush administration, and the architect of Obama’s shadowy, controversial drone program. But for all that, he remains largely unknown, the gray heart of United States national security policy. Of the dozens of former and current government officials I reached out to, men and women from both the Bush and the Obama administrations, few seemed to have a handle on him. Some saw him as strong and principled, a warrior-priest who could do no wrong. Others saw him as a yes-man who sucked up to power and got lucky.

Several former colleagues, particularly in the CIA, refused to talk about him. He is vindictive, one explained through an intermediary: “He’ll come after me.” Another initially agreed to chat and then emailed me back a few days later, writing, “Unfortunately, I learned today that, because of my active security clearances and continuing work with the intelligence community, it would be best for me to decline your offer of an interview.”

Brennan himself was of little help. Through a spokesperson, he declined multiple interview requests over a series of months. Two years earlier, I’d argued that he was the wrong man for the CIA based on his counterterrorism approach in Yemen. But now I wanted to get a fuller sense of him, both as a person and as a director, and look at his entire career rather than just a single country. Brennan wasn’t interested. Even relatives were off-limits. At one point I sent his older sister a three-line email, explaining who I was and asking if she “might have some time to answer some questions about him and what he was like as a kid.” She never wrote back. But the next day I received an email from the CIA’s head of public affairs warning me against “harassing the director’s family.”

And yet in almost every public speech he’s given over the past 10 years, Brennan opens with a smattering of personal anecdotes, little crumbs of biographical detail that, along with everything else, form an almost kaleidoscopic portrait of the man and the country he serves. It all depends on the angle, the subtle shift in emphasis that changes everything: inside government or outside, friend or foe, enhanced interrogation techniques or torture, signature strikes or crowd killing, patriot or criminal.

This is Brennan’s story, his life and his career. But it’s also ours. The excesses and mistakes of more than a decade of war, what we tolerate and what we don’t. What we’re willing to forgive and what we won’t. Politicians who don’t deliver on their promises, and well-intentioned individuals who bring about great harm. It’s about the man he is, and the country we’ve become. The institutionalization of a post-9/11 national security state, and the unending compromises of a country always at war.

The origin story Brennan prefers, the one he tells reporters, goes something like this: One day in the spring of 1977, during his senior year at Fordham, he was riding the bus to class when he came across a CIA recruitment ad in the New York Times. Brennan was intrigued. He liked history and he liked to travel. Back from a year abroad in Cairo, Brennan had already applied to graduate school, but even he seemed to know he wasn’t cut out for academia. “He never struck me as someone who would go on and get a Ph.D.,” John Entelis, one of his professors, told me last fall. “He just didn’t fit the mold.”

On a campus filled with what another of his former teachers described as “well-groomed hippies,” Brennan fit right in with long hair and an earring. He blended in within the classroom as well, rarely raising his hand or trying to make a point. To his professors, Brennan still carried himself like the jock he had been in high school, like someone who hung out near the back of the room and didn’t appear comfortable speaking in public. “He wasn’t intellectually aggressive,” Entelis said.

But that year in Egypt had given him a case of what Brennan would later call “wanderlust.” And that is why in the spring of his senior year, weeks away from graduating, he was so intrigued by the ad. Even his birthday, Brennan often explains in interviews, seemed to fit. Nathan Hale, often considered America’s first spy, was hanged on Sept. 22, the same date Brennan was born.

Hale was 21 the day the British executed him in what is now upper Manhattan, less than eight miles from Fordham’s campus. Brennan was the same age that spring. Completing the circle was the fact that Hale was born in 1755, Brennan in 1955. For an undergraduate with a romantic sense of history, the parallels must have been powerful. In many ways, this appears to be how Brennan views himself: Hale’s successor and heir — patriotic, idealistic, and willing to do whatever it takes to serve his country.

Three years after that day on the bus, following a graduate degree in government from the University of Texas and wedding the woman he took to his college graduation, Brennan walked into the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia, as a career trainee making just over $17,000 a year (a “GS-9” on the government’s “general schedule” pay scale). Two of the CIA’s four directorates, the Directorate of Intelligence and what was then called the Directorate of Operations, got most of the attention. These were, respectively, the analysts who stayed home and the case officers who worked abroad, or in rough agency slang: the nerds and the jocks. Brennan had little doubt. He was a jock.

That lasted around a year. In 1981, Brennan switched to the intelligence side. Of the people who eventually agreed to speak with me, several had theories for the move. Like their views of Brennan himself, some were dark and others more innocuous. But none of them knew for certain. Brennan didn’t talk about it and they didn’t ask. “It was unusual,” one of them told me. “But not unprecedented.” The recruit who had once dreamed of operating abroad was now a deskbound analyst, a nerd.

The CIA did, however, send him to Saudi Arabia for a couple of years as part of a joint program with the State Department. But that wasn’t quite the same. Instead of a covert program with the CIA using the State Department as cover, this was an open one: CIA analysts working as foreign service officers. The State Department, which never had enough people to go around, got a free body, and the CIA got some time abroad for its analysts, who often spent most of their careers in Langley.

None of this, however, stopped Brennan from later suggesting to co-workers that this had been a full-fledged agency position. It was one of those habits powerful men often acquire, revising and editing their stories as they go, shaping everything to fit their audience of the moment. Bosses who had never championed Brennan in life were transformed into mentors in death, and small exchanges took on the flavor of intimate conversations. People who didn’t know Arabic were convinced he spoke the language fluently; Republicans he worked with thought he was one of them, while Democrats left the conversation thinking he was theirs.

By the time Brennan got back to Langley in 1984, the agency was undergoing a culture change. “Loyalty to individuals assumed a much greater role,” wrote former CIA analyst John A. Gentry in a biting critique published years later (and removed from the internet soon after Gentry declined an interview for this story). “Those who adapted to the new rules,” Gentry continued, “experienced often meteoric rises.” Brennan adjusted quickly, finding mentors and winning promotions.

“To get ahead in the Directorate of Intelligence you had to do three things,” Judith Yaphe, who worked in the same office as Brennan, told me. “You had to write well, brief well, and get along with others well. And John knew how to do all three.” Other co-workers noticed a similar set of skills. “John’s got a very good political sense of what people want,” said one former CIA official who worked with Brennan and requested anonymity to talk about a former colleague. “John is very good at managing up.”

For the next few years, Brennan did exactly that, as he worked his way up the agency ranks. The older men who ran the division liked him. Brennan seemed to remind them of a younger version of themselves, and they rewarded him for it with promotions and plum assignments. They saw him as a “rising star, an up-and-comer,” the former CIA official said.

Brennan came into the agency in 1980 as a Middle East specialist in what would turn out to be the final decade of the Cold War, the CIA’s main focus since its founding. Once inside, Brennan started spending time on counterterrorism, a new subfield that few really understood. The CIA established its first counterterrorism center in 1986. Within four years, Brennan was running terrorism analysis for the center. A decade later, the Middle East and counterterrorism, Brennan’s two specialties, would be at the center of a revamped CIA. And, in time, so would he.

To get there, Brennan needed the help of two men: George Tenet and Barack Obama. He met Tenet in the mid-1990s when they were both at the White House, Tenet as a member of the National Security Council and Brennan as the CIA’s daily briefer to the president. Two decades later, just after the 2008 presidential elections, he met Obama for the first time.

Both times the meetings came at just the right moment: before Tenet moved to the CIA and before Obama went to the White House. Each was looking for a guide, someone they could trust. And Brennan made sure he was exactly what they needed: a perfect deputy, loyal and devoted. “John knew how to show his superiors ‘I pledge allegiance to you,’” one former co-worker told me.

In 1995, when Tenet left for Langley as the CIA’s deputy director, he took Brennan with him as his executive assistant. The two went well together, patron and guide. Tenet gravitated toward the big issues as he learned how to navigate the CIA’s hallowed seventh floor — where the CIA’s top officials have their offices — while Brennan handled the details and protected his boss. “John was George’s alter ego,” said John Rizzo, a longtime lawyer at the CIA and author of the memoir Company Man, who worked extensively with both men. “He was Tenet’s eyes and ears to the rest of the agency.” Other former senior CIA officials were more blunt: “Brennan is a creature of George,” one of them said. (Through a spokesperson, Tenet declined a request for an interview.)

Later, during a stint as Tenet’s chief of staff, Brennan became notorious for asking, “How will this affect George?” according to an article in the Los Angeles Times. The closer the two became, the more Brennan seemed to conflate Tenet with the agency he ran. Loyalty to one meant loyalty to the other. Tenet was the CIA, and it was Brennan’s job to protect him. “Brennan is a very good staff officer,” the same former senior CIA official explained to me. “He’s detailed, and incredibly hardworking. His whole life was serving the principal.”

Brennan followed Tenet up the agency ladder, rising alongside his patron. Tenet would eventually make director and, just before that in 1996, Brennan asked for a promotion of his own. Sixteen years after he’d started at the CIA, Brennan still wanted to be a spy. That’s what had attracted him all those years ago on the bus to Fordham, and that’s what he wanted now. In 1996, Tenet gave Brennan his wish, and made him chief of station in Saudi Arabia. Much like Brennan’s initial move from operations to intelligence, putting a career analyst in charge of a station was unusual although not unprecedented.

But there was a bigger problem. On the government pay scale, Brennan was a GS-15, making somewhere between $70,000 and $90,000 per year. CIA station chiefs are members of a separate pay scale, called the Senior Executive Service, and at the time they were making more than $123,000 per year. Brennan didn’t need just one promotion; he needed three. And that was unprecedented. “I’d never heard of anything like it,” one former senior CIA official told me. Tenet was playing favorites.

On June 25, 1996, shortly before Brennan arrived in the kingdom, a truck bomb struck the Khobar Towers, killing 19 American servicemembers in one of the deadliest terrorist attacks against the U.S. at the time. A few weeks later, Osama bin Laden faxed out a fatwa, declaring war on the United States. Few had heard of bin Laden at the time, and almost no one paid attention to his statement. According to multiple intelligence officials who requested anonymity to talk about classified operations, Brennan’s tenure in Saudi Arabia — like much of the CIA at the time — was marked by caution and convention. He walked a careful line with the Saudis, not wanting to push them too hard.

In early 1998, while in Saudi Arabia, Brennan helped convince Tenet to pull the plug on an agency operation to capture bin Laden. Brennan favored a Saudi effort, which was still in the works, to convince the Taliban to expel the al-Qaeda leader from Afghanistan. But the Saudi talks with the Taliban eventually broke down. The CIA never got another opportunity to capture bin Laden. Years later, Brennan defended his actions, telling a congressional committee, “I didn’t think that it was a worthwhile operation and it didn’t have a chance of success.” Besides, he added, “I was not in the chain of command at the time.”

When Brennan did finally get his chance to take part in an actual operation, al-Qaeda wasn’t even the target. The CIA had put together a disruption campaign aimed at Iranian intelligence, and, according to Tenet’s memoir as well as a U.S. official working in Saudi Arabia at the time, Brennan was supposed to approach one of their agents on the streets of Riyadh and ask if he wanted to work for the U.S. The CIA shadowed the agent for weeks, tracking him back and forth to work and planning the confrontation. But the closer the operation got, the more worried Brennan became. According to the same U.S. official, Brennan asked an FBI agent to borrow a bulletproof vest. “John,” the FBI agent said, “he’s not going to shoot you; he’s going to laugh at you.” Brennan blanched, but insisted.

On the big day, Brennan approached the Iranian’s car and said, “Hello, I’m from the U.S. Embassy, and I’ve got something to tell you.” The agent jumped out of his car, said something about Iran being a peace-loving country, and then sped off.

“That’s not how you recruit an agent,” Lindsay Moran, a former case officer in the Directorate of Operations, told me. “Historically, a number of bad things have happened when an analyst has been put in charge of a station.”

At Brennan’s going-away party in 1999, Ambassador Wyche Fowler Jr., a white-haired political appointee and former senator from Georgia, who stood on tradition and spoke in a nasally Southern drawl, gave a glowing retrospective of Brennan’s three years in the kingdom. Sitting at tables in the ambassador’s massive dining room, the men who worked with Brennan on a daily basis tried to square what they were hearing with their own experience. “It was like he walked on water,” a U.S. official who attended the event later told me. “It sounded like John was a god.”

Toward the end of his remarks, Fowler’s voice started to crack and his hand moved toward his eyes as if he might cry. “It was so over-the-top,” the former U.S. official told me. “We were almost embarrassed for him.” Another agent whispered: “Is he drunk?” But that’s how it was between Brennan and his supervisors. He knew how to manage up.

https://www.buzzfeed.com/gregorydjohnsen/how-cia-director-john-brennan-became-americas-spy-and-obamas?utm_term=.jfJBqg92Q#.hdBNgrjbv